Inquiry Behavior In Trade Publications

The subject of inquiries to advertising is a topic that is always interesting. With the advent of the Internet, the topic has gained another emphasis and subsequent debate over their quantity and value “in the electronic age.” This is especially true in trade publications in the business-to-business environment. This is because of the “value” that is placed on the inquiry itself; in the business-to-business world, lead cultivation often takes months, sometimes years. Finding and setting up these relationships is critical to the advertiser who often uses two-step distribution to deliver his products to markets.

Inquiries that spawn relationships in a trade publication are often directly tied to a specific media, and to advertising in particular. But in the last decade, advertising (and media) has undergone profound – and irreversible – changes. Whereas in the past, trade publications produced leads on a steady basis, collected them and reported them to advertisers, the Internet has shifted this “contact” process and production of inquiries to other channels – or so it is believed. Prior to the Internet, readers of trade publications could call the company from a phone number in the ad, call a company’s sales representative (if they knew them), or circle what is called the Reader Service Card. This device was bound into the magazine, and afforded the reader a means of getting more information from the advertiser. And while the same contact channels were true of other media (television, radio), the Reader Service Card was almost exclusive to trade publications (some consumer magazines used it to great benefit as well).

The Internet has changed all this, and publishers are using it to eliminate this contact channel (the Card). The purpose of this report is to explore the effects of this occurrence, and to discuss advertising response behavior that it has caused. This paper reviews, therefore, the Internet’s impact on trade publication lead generation in general through our study of hundreds of magazines over the years (we receive over 1,000 publications in our offices each month). While Accountability Information Management, Inc. (AIM) draws from its 20+ year history of tracking leads and readership in a variety of publications, we highlight numbers that are representative of many trade publications’ behavior patterns knowing that some will be “more” and some will be “less” in terms of inquiry production. We also utilized in this paper the history of inquiries (as we have from other publishers we have worked for over the years) as a benchmark. The magazine we utilized still maintains its Reader Service Card, and as such, serves as an example of what would be lost if it disappears. To start the discussion, it is important to clearly understand the steps that lead toward the production of an inquiry itself.

Overview

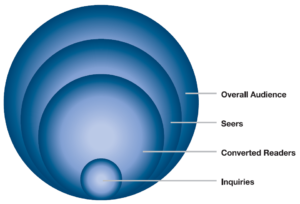

There are basically three behaviors that a reader can take when an ad appears in a magazine (and while this is true of any ad on the Internet, television, etc. for that matter, our focus is the ad in trade publications). These three behaviors that happen are always in the same order, though that order can break down and collapse preventing the next behavior from taking place. What breaks these behaviors down is part of the subject matter of this report.

The behaviors themselves are: seeing, reading and acting. By “breaking down” we mean that the reader might not see the ad, and therefore will flip the page or move toward another part of the page. The reader after seeing it might not read the ad, and slip or move on, and after reading it, might not act to the ad. The first part of this report will examine these behaviors in depth and in relationship to the Internet’s effects on the behaviors. After this, the paper will deal with specifics about inquiries based on Reader Service Card analysis. Let’s look closer at these three behaviors.

1. The ad is seen. Whether or not an ad is seen is caused by the creative execution, and as will be shown, is strict size related. Whether or not the ad is seen by the “right” people in a trade publication environment has always been the magazine’s responsibility. Today, the “right” people bring to light one of the immediate problems in the study of inquiry behavior: who are the right people? As influencers, purchasers, users, decision- makers begin to blend . . . as functions like architect, owner, distributor, representative become entangled in making a final purchase decision or recommendations and in the actual roles played by these professionals — the advertiser, as well as the publisher, is faced with the task of defining and targeting “right.” In the past, segmenting the audience was simple; often, trade magazines emerged surrounding these decision makers. For example, a magazine that seeks to go after architects builds a circulation of architects, or a magazine going after building owners builds one of building owners. Some magazines elected to do a horizontal strategy; that is, take segments of more than one important audience.

But as responsibilities of the readers become diluted and shared, today’s era tends to hide the “trigger-pullers” and makes it difficult to find the right targets. This places enormous pressure on publishers to deliver audiences to maintain their advertising base, and is, in our opinion, one of the fundamental reasons why ad pages are dropping off so much. Frankly, many publishers have left behind their circulation strategy and gone head over heels at the Internet. This move besides diluting the potential for the ads being seen by the “right” people, directly affects the number of inquiries that can be generated. Quite simply, the less people that get to see it, the less that can read it, and the less that can inquire. Not all publishers neglect their circulations, as will be evident in this report. But, those who do in favor of the Internet directly impact the number of leads that come through the magazine’s channel.

Furthermore, one can also see another immediate problem the Internet produces in understanding inquiry behavior: users of websites are largely unknown unless prior registration is a requirement of a website. The Internet makes it so easy to obtain information, that literally, finding something you are looking for becomes possible, probable and extremely simple. Trade magazines were built around people with similar interests, creating an environment where an advertiser seeking to reach such people found fertile ground. As these circulations become diluted with sometimes two- or three-year names (found on the BPA/ABC statements), it is only natural that response drops off – a situation which presents yet another problem: what is advertising itself since as content blurs, so does the separation between what is and what is not an ad?

In trade publications, it is relatively easy to differentiate what is an ad from what is an editorial. There has always been the “advitorial” in which the advertiser took advantage of the publisher’s offer to create something that “looks” more editorial. But as circulations disappear, publishers are more open to other- than-ad creative to keep up their revenue streams. Belly-bands, special supplements, custom published opportunities are created further confusing readers as advertisers strive to break through the growing clutter.

Indeed, “being seen” has always been associated with breaking through clutter, and there’s certainly no shortage of clutter these days. For example, as magazines shrink in size, the Internet explodes in more and more data. Experts at the San Diego Supercomputer Center say that computer users world-wide generate enough digital data every 15 minutes to fill the U.S. Library of Congress. According to an article in the Wall Street Journal, more technical data have been collected in the past year alone than in all previous years since science began. Metamend Software & Design Ltd., a leading search engine marketing firm in the industry, notes there are 17 billion web pages of content on the Internet. To put that in perceptive, if you piled the paper equivalents of the web pages one on top of the other, you’d have a stack of paper 11.5 miles high, weighing about 187 tons. No wonder publishers are abandoning print! Who has the time to “see” all these pages, and how do you determine who is seeing them? Moreover, which of the pages are true, which are advertising? How do you “break through?”

Trade publications have always tried to identify their audience and therein lies one of the essential differences between being seen on the Internet or in a trade publication: in the magazine, you used to know who was looking at you. If a publisher maintains a qualified circulation, the advertiser always had a good idea of who was out there. On the Internet, however, that’s never the case, unless you have a pre-registration sight like a Wall Street Journal. So what many trade publications use are independent audit companies like BPA or ABC to verify the receipt of publications, thereby giving the advertiser some assurance it is the “right” person. However, this exercise does not guarantee the “right” people will see the ad; it only means that the publisher has met the organization’s standard for delivering the audience it says it delivers.

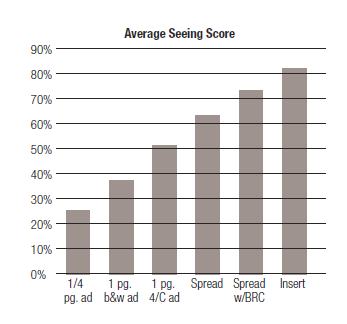

The physical act of “getting seen” resides, as mentioned, within the creative execution of the ad itself. AIM’s analysis of over hundreds of thousands of seeing and reading scores from research companies that conduct such studies gives us a simple truth: size matters when it comes to breaking through clutter and being seen (see chart).

Chart shows average seeing scores by size of ad for one year in a publication. It is typical of publications.

The larger the ad, the more likely it will be seen. The smaller the ad, the less likely. While this may seem like common sense, it is verified by the data.

It is important to state at this point that “seeing” has nothing to do with the next behavior, “reading.” As will be demonstrated, size strictly matters in attracting attention of more eyes – not in whether the content is digested or not.

Also, keep in mind whose eyes we are talking about. It becomes costly for a publisher to maintain what they believe is the “right” people in their circulation. That is because “right” has changed. More and more people influence a purchase decision, making relationship building between a magazine’s content and readers tougher. Publishers will argue that they have a relationship with their audiences, sometimes called affinity, but that, too is under pressure as that audience is bombarded by the content on the Internet. Publishers are torn between providing their content in print, or online. That conflict produces a lot of misinformation about how people get information, and as a result, the effects of advertising within that information.

Publishers are evolving “web communities” and trying to extend their franchise to the virtual world, often at the cost of their print side. The problem with that strategy is that virtual audiences and print audiences are different; not only is the “mode” in which the advertisement is delivered different, but WHERE the person is and what that person is doing while he is interacting with the media is different. What you can do in print versus what you can do on a website are, in fact, dramatically different, suggesting different creative strategies be employed.

The time you spend on a website or looking at advertising on a website is dramatically different from print, as are the techniques for capturing attention or “getting seen.” The time you spend on websites in seconds, whereas in print, the time is much longer. Sappi, a manufacturer of fine paper, produced a brochure about the benefits of print, and it would be helpful to review one of these for the purposes of this discussion of seeing advertisements. They argue that magazines are a perfect device for advertising because they can target a specific audience and “speak to their readers on an individual level.” While we can say that a website can extend that individuality by making the reader “register,” and then customize the content totally to the reader, what you lose by doing that is the ability to browse and take in other-than-what-you-want. When you “customize” and serve yourself what you want to be served, you lose any chance of seeing something you don’t want. What you “never” want is an “ad.” From an advertising point of view, the Internet is diametrically opposed to the concept of advertising, which inherently has at is roots presenting information on something that you might want now or in the future. In a magazine, not all content is customized to the individual – just to the individual’s interest. There is a certain “freedom” associated with publisher/editor selected content in a magazine that is not present on the Internet (even Google attempts to help you customize your view of the Internet through itself).

Sappi’s brochure also said that readers spend an average of 45 minutes examining an issue of a magazine – a fact that the Magazine Publishers of America promote. That’s a long time by any standard, and there have done studies where that translates directly into the amount of time people spend on the products and services being advertised. Erdos and Morgan, a research company, is one of those that showed that magazine readers were more often purchasers of a product as a direct result of the advertising than were people who looked at television, cable TV or the Internet. Furthermore, magazine readers were seven times more likely to do such purchasing!

Put it this way: going on the Internet, people generally have an idea of what they are looking for; browsing through a magazine, they allow the content of the magazine to “suggest” what they should be looking for. Suggestion is the essence of advertising. The point is, therefore, that “seeing” is a function of the media you are in, and the advertiser must make judgments on where to spend his/her communications dollars. It makes sense to spend it on where more time will be spent, or where the vehicle itself is the essence of advertising: the magazine.

For example, a company seeking to influence business decision makers may select a television commercial, a billboard, or a magazine as a probable way to reach the “right” people. These would, in turn, be selected based on the “audience” that is projected to be around them; that is, maybe purchase the TV around a business show as opposed to Seinfeld, or BUSINESS WEEK as opposed to running in BETTER HOMES & GARDENS. As elemental as this sounds, it is the core of media selection: picking the right media for the intended purpose with the right audience; however, there is still no guarantee that people will “see” the advertisement.

In BUSINESS WEEK, as a matter of fact, one of the highest recorded “seeing” scores was 99% for a company that ran a pop- up insert within the magazine; that is, when the reader turned the page, the insert opened up to reveal an entire city! This means 99% of the circulation of BUSINESS WEEK saw that ad. What is remarkable is that 1% missed it. How do you miss a pop up in a magazine? Simple: you don’t read the magazine. Therefore, it is always possible to ”miss” part of the circulation, regardless of the ad’s size. Suffice to say that AIM studies over the years indicate there is a strong correlation between size of ad, and the number of eyeballs that the ad captures (see earlier bar chart that demonstrates the relationship of size to seers). Before leads can be produced, therefore, the advertisement MUST be seen.

2.The ad is read. After being seen, the ad can be read. The magazine is responsible for having the right people available as discussed in qualifying circulation. Some will argue, now, there are differences between “paid” circulation and “qualified.” However, for lead generation purposes, we will treat them the same for the following reason: paid or qualified, when a person shows “interest” through inquiring on an advertisement, it really doesn’t matter if the lead was paid or qualified. As evidence, trade publications today are supplementing their leads provided to advertisers with what they call “bonus” leads. The reason is the Internet’s impact on number of leads being generated on the advertisements themselves; the Internet actually LOWERS the number by freeing up the reader to go directly to the advertiser’s website. Moreover, as many publishers are eliminate the Reader Response Card in an effort to cut costs; they figure, incorrectly, that since the advertiser is largely responsible for “handling” the lead, the publisher can “cut costs” and simply re-direct his audience to the advertiser’s website.

This elimination of the response channel is suicide for the publisher, because unless the advertiser has equipped himself to measure response, there is no way to tell where the inquiry comes from. The Reader Service Card is one of the few remaining ways to verify the quality – or lack of quality – of magazine’s audience. For example, one publisher – and early adapter of the Internet – had great control over his circulation to the point that he personally hand-crafted that circulation, assuring himself that the readers of his magazine were exactly what he told his advertisers he had. Once satisfied, he eliminated his reader service card. His sales representative sold a schedule to one of our clients, and after six months, our client was wondering where the response was. We had to report “none,” as we had no way of measuring it. A conference call ensued, where the publisher argued strongly about the quality of his circulation.

While he convinced us of that quality, we had no way of demonstrating it and would be forced to pull the remainder of the schedule. The publisher asked what he could do to “save” the account, and we said, “put back the reader service card.”

After more discussion about the costs involved, the publisher agreed to a compromise: to bind in a reader service card at our client’s ad. We told him we would report back the results. The first inquiry to emerge from his circulation was the managing director of one of the largest fast-food chains in America – exactly the target he said he possessed, and exactly the target our client wanted. We received over 160 cards back from this effort, and the publisher was so convinced on the value, that he re-instituted the reader service card for his publication (other advertisers were also complaining to him why they couldn’t have a card like our client, too!).

This is not an isolated case, but it speaks to the need for keeping the channel open, and having metrics in the background ready to measure what comes out of a publication. Therefore, the ad itself – not the magazine — is responsible for converting seers into readers.

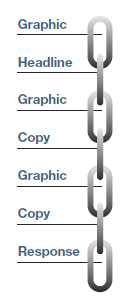

Measurement of this step is Accountability Information Management’s (AIM’s) contribution to the understanding of advertising behavior, and is built into the databases we have created for numerous magazines and on our 1990 article, “Behind the Numbers” which appeared in Marketing Research magazine. This AIM Ratio (a calculation of how many people go on to read the ad AFTER they see it) was subsequently used in Starch readership studies as “Readership Ratios.” Reading, as we will see, is required in order to ensure an inquiry can be developed, and is part of the Readership Chain we have developed. Before discussing that Chain, remember that reading habits are different today from years ago. In fact, reading habits change continually. For example, more magazines and newspapers were published in the 1960s than prior to the 60s. This is when eye-movement and reading studies were conducted (the first studies using eye movements to study the processing of ads appeared in the 1960s conducted by the famous Daniel Starch). They found then that reading was more rapid and skimming occurred more often than in the past. Today, with the Internet and texting and television, this skimming has been accelerated, making it even harder for an ad to secure attention much less be read.

Perhaps more important, we must ask if the “need for speed” has diminished the importance or “need for comprehension” through reading. It cannot be argued that comprehension diminishes as skimming increases. An analogy is listening to Mozart at 3x the speed of the original song, or listening to any music at 3x or 4x the speed. Comprehensive and appreciation diminish accordingly. Thorough understanding indeed can not take place unless attentive reading takes place, and this means that a proper amount of attention must be paid to the subject matter.

But that is the world in which advertising operates today. The number of advertisers and ways to advertise has greatly increased. Consequently, it is more difficult to attract attention to enable reading to take place.

The Readership Chain illustrates this, and shows the de-linking taking place in today’s fast paced reading climate. In the past, there were more links of “copy” and “graphic” which, by the way, illustrates that the chain itself is expandable. When reading a book, for example, the “graphic” of the advertisement is replaced by the “imagination” of the reader, who often pauses or unconsciously paints pictures as words are comprehended. In a print advertisement, the importance of the graphics and copy cannot be underestimated. The reader is attracted by the graphics, reads the headline, goes back to the graphic, starts the copy, checks the graphic, reads the copy and then finally responds. If any of those “links” are broken, nothing happens: the page is turned.

So, why do people read ads? Do they read ads? There are numerous studies that put forth reasons and answers to these questions, but the fact of the matter is that people read to do one of two things: 1) gain something, or 2) protect what they have. Bob Stone, one of the fathers of direct response, said this about reasons why people buy things, and it is also true of why people read anything (if they read any longer). Reading advertising is not really different. Therefore, what must exist first is the inherent interest in the topic being presented.

The fact that this interest cannot be measured per se is one of the reasons for “qualified” circulation. Publishers gather similar people with similar interests around a topic and publish a magazine geared to those people. But what is important to understand is that the act of reading is NOT related specifically to the size of the ad: on a ratio basis, a smaller ad can have a higher readership than a larger ad. What traditional readership studies neglect is that ratio, the implication being a larger ad has higher readership. This is simply not true.

For example, a small ad may have a seeing score of 10%, and a raw reading score of 5%. This gives is an AIM ratio of 50% — that is half the people who saw it went on to read it. A larger ad may have 20% seeing, and a raw reading score of 10%. This AIM ratio is also 50%, and while we can say that “more” people read the larger ad from the circulation because of the percentages, the effectiveness of the readership is the same. The smaller advertiser simply has to grow his/her ad in order to capture more potential readers. A close examination of readership studies not only demonstrates this; it proves without doubt that smaller ads many times out pull larger ads in readership and, as can be shown, inquiries. This result demonstrates that there exists a relationship between reading and inquiring, more so than any relationship between seeing and inquiring.

In summary, reading is the responsibility of the creative part of the ad, and also the publisher’s responsibility to bring people of the same interests together (by the way, that is what inherently paid circulations do, since why would anyone pay for a magazine that doesn’t interest them?). The remaining part of this paper deals with response, the ultimate goal of any advertisement.

3. Finally, an action takes place. A magazine is accountable for helping deliver the action (in the form of the inquiry) to the advertiser, and the ad itself is responsible for providing vehicles to respond such as websites, 800 phone numbers, FAX numbers, etc. Ads get acted upon by only some of the people who read them. This is why the readership number provided by the AIM ratio is important; it can provide insight into people who have read the message, but may not have an immediate need and hence to not immediately respond.

People have debated “exposure” versus “response” for years, and some settle for exposure. However, response it the goal of advertising; nothing happens until you sell something. The underlying goal of advertising is to penetrate the minds of targets with exposure so that when the need does arise if it isn’t present when the ad is read, the target will “remember” the company and take the appropriate action (purchase) when the need does arise. Therefore, knowing the readability of the ad is important, and the AIM ratio gives us that measurement.

How people take action is important to understand. For example, while many companies provide 800-phone numbers, not all companies provided 26 different phone numbers to measure the advertising in 26 different trade publications, as we did for a client. These “direct mail” type tactics are important to not only understanding response, but in shaping better response by enabling people to respond the way they want to respond. Historically, the reader service card was the vehicle of trade publications to deliver inquiries to advertisers. With the use of the Internet, however, that is changing. As pointed out earlier, the use of the Reader Service Card is diminishing; readers often find it more convenient to go direct to the advertiser’s website, or calling up the advertiser.

But, not all publishers have abandoned the card. Inquiries off of the Reader Service card remain one measure of this inquiry puzzle, and frankly, hold clues to understanding response and inquiries. To truly measure response, all forms of feedback must be accounted for. Which bring us to the discussion of why people respond and inquire to ads at all.

Why People Respond

There are many reasons why people respond to advertising. There have been many papers written on the topic. But the simple matter is that people respond for the two reasons Bob Stone mentioned: to protect what they have, or to gain something.

In essence, people respond because they have a need. Like Pavlov’s dog, a bell rings and they are urged into action. Response to stimulus is an ongoing problem to advertisers, which is why the advertising world is under siege. Frankly, there are too many different bells that can ring, and with the customizable options in play today, people can change the tones of those bells at will and the advertiser never knows it even happened. Together, these present the advertiser with a huge dilemma: which bells do you ring?

Some clues can be found in a lot of the research published on these topics, but many of these are academic studies that do not account for real-world observation – or action. For example, Simon Broadbent is one of the more famous media folks who wrote a book called “When to Advertise.” In it, he argues that the primary use of a concept called Adstock (The impact that advertising has over time on sales or awareness) is for establishing the media budget, not spreading the dollars. There are a lot of excellent calculations in those pages, but so what? None of the “science” contains that magical part of advertising that almost defies the science: determining exactly 2 + 2 = 4. Why? Because it isn’t just a science! Advertising an art form as well. Just ask any direct response professional.

Direct response is simple: 100 sent out, 10 back, 10% response, 1 sale, 1% conversion factor, or 10% based on the 10 you got back. How do I improve that? Direct response people test continually to beat the “control” as they call it, and figuring out why people respond includes understanding their “hot button,” and the timing of the offer more than “how” the sale is presented. But, to generate any kind of response, the advertisement has to be seen and read; otherwise, nothing happens. Therefore, understanding why people respond requires an examination of what gets ads seen and read (as we have discussed), as well as the follow-up to the response! In other words, a study of inquiries and why they respond would be the best way to measure response.

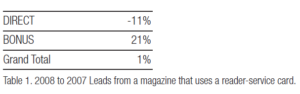

Impact of Internet. The age of the Internet has dramatically re-shaped lead generation – not the quantity, but “how” inquiries are made and followed up upon. In this example, we will begin to clarify the confusion around leads. For example, many publishers explain to advertisers that lead generation has fallen off since the advent of the Internet. Advertisers, on the other hand, complain about the same thing: that leads have fallen off. This is why many publishers underwrite the dropping off through the print channel with what is termed “bonus” leads. But have they? Or, has the “channel” of the inquirer changed? Consider the following table:

The table presents a comparison of the many thousands of leads generated over a period of two years: 2007 versus 2008. While direct leads (to advertisements run by advertisers) has fallen off 11%, the bonus leads (leads collected and given by the publisher to advertisers in specific, related areas) has risen 21%. The net effect of this is a 10% gain to advertisers! Moreover, 2008 actually produced overall 1% more leads than 2007. So why do advertisers complain about leads falling off?

One company we studied several years ago when bonus leads started taking shape had more successful equipment placements on the bonus leads than on the leads that were directed at their advertisements! This taught us that regardless of WHERE the lead comes from, it is the follow-up that is the more critical factor to turning that lead into a customer.

In a separate study, AIM conducted a comprehensive follow-up study where we circled “bingo numbers” for information in a magazine. We circled EVERY number using separate cards (to avoid the publisher throwing out our cards as a hoax). Here are the results of that study for your consideration.

- 30% of the advertisers responded to our request for That means 70% paid no attention to our request!

- The average response time for the 30% who responded to our request was 37

- The average creative costs for the print material we received is estimated (at $1,500 per page, conservatively) to be $113,152 each. The range was between $1,500 for a small 8 1/2 x 11 brochure, to $576,000 for the following we received from one advertiser: — 2 Four-color pamphlets — 3 Four-color catalogs (100 pages, 64 pages, and 200 pages) — 1 post card

- The total creative costs for the 30% who sent things back? $2.5 million – NOT including printing.

- After the initial fulfillment, three of the 82 companies sent follow-up That’s 4% who did ANYTHING resembling follow-up!

- We lost $92. Some of the advertisers charged a nominal fee for what they We wrote personal checks for this material, which we did NOT receive. What should people feel after THAT experience?

We repeated the experiment a few years later with similar results (response had risen to 40%, but the average days to receive literature climbed to 44 days).

One reason for the lack of follow-up is that the Internet gives readers much more freedom to “visit” the advertisers directly online. In the past, besides circling reader-service numbers, prospects could call an 800 phone number or FAX an advertiser. Today, the prospect can do all that, but also hop online and visit the advertiser’s website. This puts the responsibility on the advertiser to “track” this activity – not the publisher. Just as in the past, an advertiser would dedicate an 800 phone number to a specific advertising campaign, the advertiser today should be creating “landing pages” to collect traffic information from advertising. If the advertiser doesn’t do this, the results get lost.

This lack of follow-up also is a main reason for advertisers’ complaints about leads falling off; they watch “the numbers,” and forget that response to those numbers often determines the true number, or that the shape and content of the advertisement itself can drive numbers up or down. For example, some of our advertisements have experienced little drop in response; in fact, some the ads we create experienced increases. But this can be explained because our ads are created FOR response, not for image building or simple exposure. Our client’s advertising campaign in this magazine earned the highest number of responses in 2008; not by accident, the ads were built for reader response – and follow-up.

Yet another complaint is the “quality” of the lead itself is dropping. But here again, the complaining is based on irrationality, not logic. The quality of the lead has never been better according to our studies. Based on these studies, people do not have the time to waste in asking for information they cannot utilize. In actuality, every lead is a good lead; the basis of the complaint is usually the lack of follow-up by the advertiser on these leads, bonus or direct.

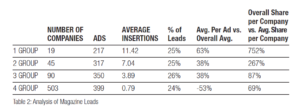

Consider Table 2. This Table shows an analysis of 2008 leads in a magazine using a reader service card. There are four groups of advertisers, which have been sliced into quarters based on total leads (Total Leads / 4 = 4 groups, each with equal totals). In other words, we took the total leads, ranked them highest to lowest in terms of inquiry generation, and then sliced them into four even quarters. Immediately you see something interesting: 19 companies control 25% of the leads. These 19 companies did only one thing different than the other groups: they ran more ads. Their average insertions were 11.4, almost full schedules. The reward? They not only control 25% of the leads coming from the magazine, their average per company compared to the hundreds of other companies in the magazine is 752% ABOVE the average per company!

This is not only remarkable; in this day and age of “skimming,” it is a testimony to the fact that people do read and respond. Since our client was in that group of 19, our follow up of the leads determined that each and every one of the responses had something to “offer” our client, whether it was in new specifications, samples requested, projects in the works. The ads followed the Readership Chain, and were noticed. Then they were read and responded to. A careful study of Table 2 will also reveal that “playing” with advertising isn’t worth it; that is, running one or two ads, a company is better off doing something else with their money. Publishers will not appreciate hearing that, but the facts speak for themselves.

Summary

Inquiry behavior has changed due to the Internet. However, the behavior of people who are seeking information has not: they seek information continually for the work they are performing, and it is up to the advertisers to harvest these leads and turn them into business.

The information is © 2018 by Accountability Information Management, Inc. All Rights Reserved. You can use the information for your own purposes, and you may 1) Reproduce it in Print or Electronic Form or 2)transmit it via E-Mail as long as you provide Accountability Information Management, Inc. credit for its orgin. You may NOT post it on a Web Site without obtaining permission. To obtain permission, contact Accountability Information Management, Inc. at the above address, or contact: Patty Fleider, ACCOUNTABILITY INFORMATION MANAGEMENT, INC., 553 N. North Court, Suite 160, Palatine, Illinois 60067. For more information, or to participate in the our other studies, contact us at the address or phone number above. Thank you.

IMPORTANT: Accountability Information Management, Inc. is in the business of managing market information. In our practice, we build databases in order to extract knowledge. We research and talk extensively to individuals involved in the business-to-business industry. We often go into detail during our conversations about not only their projects, but also their habits in terms of obtaining and using information in their jobs. This report and its contents are part of our methodology, products and services. It is copyright ©2018 by Accountability Information Management, Inc., 553 N. North Court, Palatine, Illinois 60067. This report is for the private use of the company named on the cover. Routine photocopying or electronic distribution outside of the named company and except for discussion purposes by that company is a copyright violation. Opinions expressed herein are intended to be CONFIDENTIAL. The Idea itself is the intellectual property of our company. For information on anything in this report, contact: Jim Nowakowski, 553 N. North Court, Suite 160, Palatine, Illinois 60067, tel: 847-358-4848, fax: 847-358-8089.