Uncovering Opportunities for Door Hardware Through Specification Analysis

Using Mentions, Not Projects to Gain Share and Build Awareness with Architects

To say that specifying door hardware is complex is an understatement.

Hinges, pivots and pivot hangers, mechanical locks and latches, door closers etc. can all be specified from different manufacturers! Worse, consider the following “specification” language:

“Door hardware supplier with warehousing facilities in Project’s vicinity and who is or employs a qualified Architectural Hardware Consultant, available during the course of the Work to consult with Contractor, Architect, and Owner about door hardware”.

When such language is used in specifications from companies like Walmart, it’s not just about the hardware anymore! The specification tells you where to purchase the products![1]

In the past, and perhaps because of its inherent complexity as a collection of components, door hardware specification may have been an afterthought in the mind of the architect or a “business as usual” type of specification. They are written and used over and over automatically.

However, with growing security concerns, doors and their allied hardware as one of the main access areas have risen to become something the architect and designer must start paying closer and closer attention to. Besides the natural aesthetics of door hardware, which is the realm of the architect and designer, the same door and hardware specifications take on a different point of view when it comes to safety.

Safety requirements in fact are often in direct conflict with security requirements for a building (getting people out quickly versus locking them down quickly). And, the process goes beyond just the specification. Increasingly, maintenance costs must be factored into the overall thinking – something the architect traditionally left to others.

In short, door hardware is one of the most competitive markets in the building industry.

Opening the Door

So how should a door hardware manufacturer approach the market? Especially in this age of the coronavirus, what strategy should the manufacturer employ when the face-to-face is being buried in favor of the e-conference or tele-conference?

That answer really depends on your point of view – or more accurately, the point of view of the manufacturing company you happen to be working for.

It also depends on the understanding that regardless of the imposition of “no contact” by virus concerns, if you are going to do business, some form of contact is essential to survival with the people who control the specifications: the architect and designer.

In all cases, you must start with a study of the market itself – the actual specifications written by architects. The position of the door hardware manufacturer in that market will determine the answer to those important questions about contact strategy.

Most companies look at specifications and count specifications. This report is about looking not at projects per se, but at “mentions” of a manufacturer in those specifications. In other words, more than one manufacturer competes for a project; if you are going to hatch content strategy, investigating mentions is more beneficial for a couple of reasons.

First, calculating mentions gives you an excellent overview of your competitors – not just the projects. As we will demonstrate, the currency in your battle is architects. The study of mentions will give you which architects you should go after, and which you should avoid. A study of just projects doesn’t do much for that type of planning.

Second, a study of the mentions of companies in a specification produces architects who may have neglected a door hardware specification for a long time. For example, companies merge all the time, and you would be surprised at the number of obsolete specifications written around manufacturers who no longer exist or are doing business under another brand name.

The study of mentions, along with projects, produces a new way of exploring your contact strategies with the people you need to make your advocates: the architects and designers.

Door Hardware Specifications Up Close

In the most recent ConstructConnect™ database of construction projects (where there are over 511,000 projects in the US and Canada), filtering for “door hardware” in the past 12 months results in 59,432 projects available for such a study. That’s really a lot of projects, which is why specification analysis is critical and must be done before a contact strategy. And it’s a moving number because projects come and go. Architects who command those projects come and go too (don’t forget, architects compete against each other for the very same projects you are trying to get products installed).

From the examination of these 59,432 specifications, there are at a minimum of 39 door hardware manufacturers who compete in the specifications for work (and there are probably more, but you must draw the line somewhere).

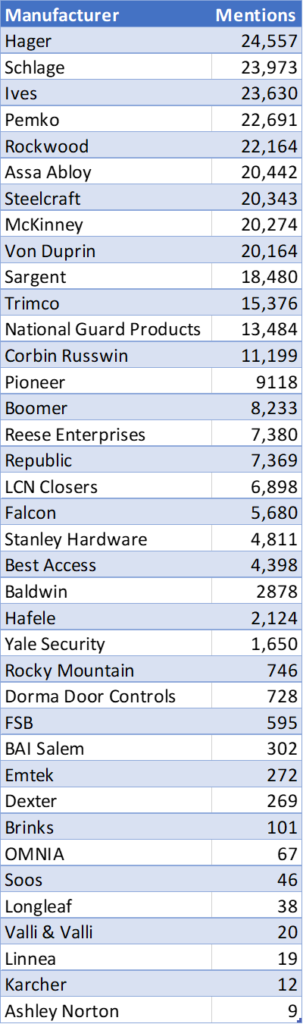

Table 1 shows the manufacturers and the number of specifications that are mentioned within the dataset of 59,432. Thus, Hager is mentioned in 24,557, Schlage in 23,973, etc. If you are running ConstructConnect, your numbers may vary depending on the license.

This table shows the number of mentions; that is, it is highly likely that more than one manufacturer may appear in a single project specification. Thus, Hager may be in the same specification as Boomer, or Schlage may be in with ten other manufacturers. This is why mentions for your contact strategy is more relevant than simply projects. While it is true manufacturers compete for a project, they are really competing not for the project, but for the architect’s specification – the mention. That is where the real battle is fought.

Table 1. The 39 Manufacturers and their respective “mentions” in specifications within the 59,432 projects.

In Sweets®, for example, there are only 31 manufacturers listed and none of these are the same manufacturers we are talking about in the current real-time dataset![2] Our 39 manufacturers within the specifications examined, then, “control” the market of door hardware specifications. Within that market are the architects who do the specifying. Your contact strategy is aimed at them – not the project.

From Table 1, you can immediately observe that only a handful of companies control most of the projects and, subsequently, mentions! If you are not one of these handful, your contact strategy for gaining share will be completely different than if you are one of them. In short, your approach to the market (answering the original questions) is dependent on your initial position within the market.

Specification is a Ground War

There is no substitute for “feet on the street.” But, where do you send your army? And when a virus like Coronavirus strikes prohibiting personal contact, what should you do? What should you look for and where should you look?

The father of strategy, of course, is Sun Tzu and his book, The Art of War. In it, he states clearly that if you are going to win any battle, you must make many calculations before the battle is fought. Generals who make only a few lose. He illustrates this by giving you strategies – strategies which can be applied to your own thinking in gaining ground in specifications.

For example, if a competitor is secure in his market and holds a strong position in the specifications, why attack? Look for weaknesses instead. Is that competitor strong in the school market and weak in the office market? What products lineup in the specifications in those markets, and is there room for your products?

Sometimes, attacking when the competition is not prepared works (i.e., in a market where he believes he holds the superior position, but doesn’t, which you can find out with some research).

ConstructConnect™ is one of the more robust databases of construction that you can use to evaluate such conditions in building your strategy. It takes time and experience to drive the database, but the analysts at AIM are experienced drivers. We looked at the door hardware market to help you explore such considerations.

Meet the Players

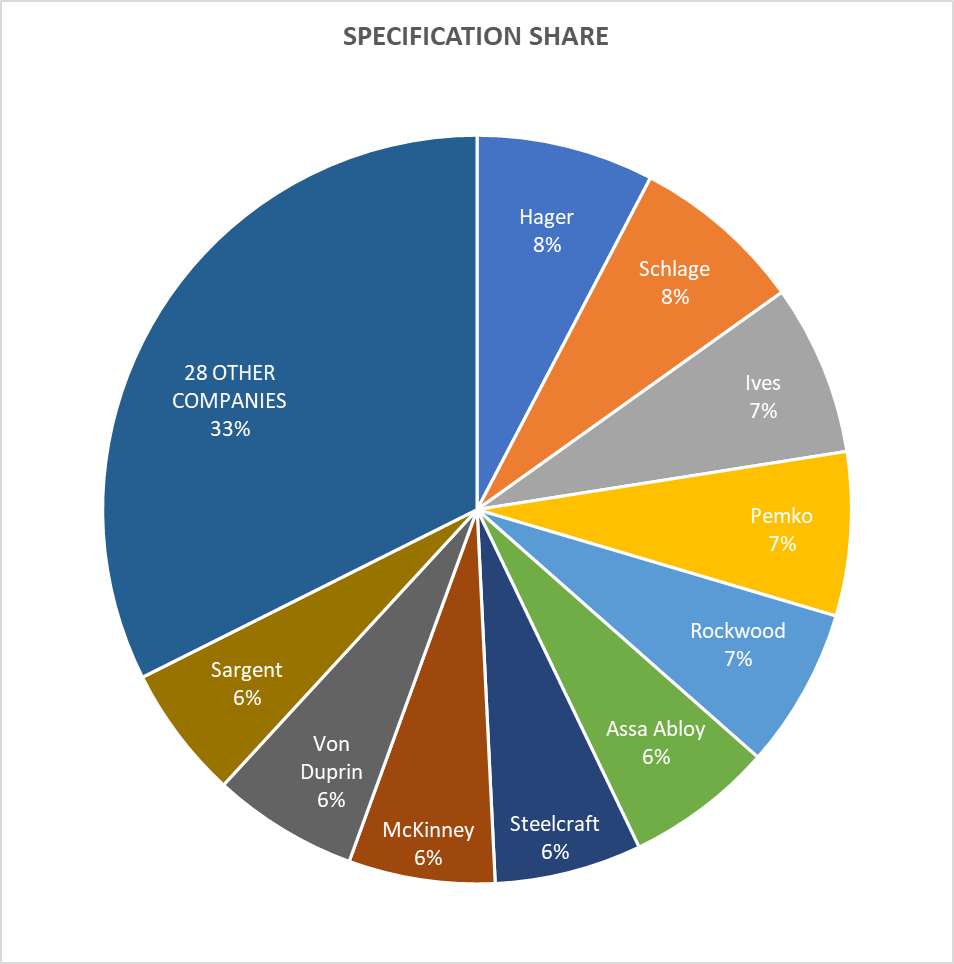

There are ten (10) companies in Chart 1 that control most project specifications and subsequently mentions, around 67%. This calculation is based on mentions in the specifications themselves (or, if there are 320,540 manufacturer mentions in the 59,432 specifications, what is each manufacturer’s share of those mentions?).

This is important because specifications typically list more than one manufacturer. Hager, for example, shows 8% in Chart 1. This means Hager, of the 320,540 mentions in the specification dataset, is mentioned in just 8% of the total mentions. Looking at just projects, it is impossible to tell how much “share” they have of projects, since we don’t know who won the project eventually. And, since as mentioned, a manufacturer can be in more than on specification, the mentions in Chart 1 give the door hardware manufacturer a more realistic view of the true battlefield. Here’s why.

Chart 1. Share of “mentions” in the 59,432 specifications, where there are 320,540 mentions of 39 door hardware manufacturers.

If you look at Table 1, you can see Hager has the most project specifications: 24,557. In other words, Hager is specified 41% of the time in door hardware specifications (keep in mind the numbers shift daily in a database like ConstructConnect™ as projects move in and out of stages).

But so does Schlage (40%) or Ives (40%). However, while they control a lot of specifications, in the battle for the specification of the architect, there are hundreds or thousands of architects writing such specifications! In the total mentions, Hager only has 8% of the mentions. Baldwin, another major manufacturer, is fighting with 28 other companies for mentions.

Thus, there are two ways to look at the door hardware battlefield: by projects, or by mentions. Mentions gives the manufacturer a clearer picture of what must happen in terms of competitors he has to fight – or decides to fight – to formulate a real contact strategy. In other words, don’t chase projects: chase architects.

The Pursuit of Architects

For example, does Hager continue to battle Schlage for specifications? Then both datasets should be examined from each manufacturer to see how many they share, and how many are unique to each company. Or, does Hager elect to go after one of the 28 other company specifications? The same questions must be answered: how many do they share, how many are unique. Then, and only then, can the attack plans be drawn.

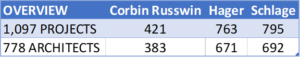

Let’s illustrate what we are talking about by looking at the top two companies in door hardware from our list, and just one of the other 28 companies, Corbin Russwin. Further, let’s only focus on the planning stage of a project (remembering we can do anything we want to determine a contact strategy). The Planning stage is always an interesting one because it contains projects that are ripe for such discussion – and for action. In this case, there are 2,439 projects in that dataset with “door hardware” as the filter. Consider Table 2.

Table 2. Three random manufacturers with project and architect counts from this sample investigation of planning projects filtering for “door hardware.”

Table 2 shows us there are 1,097 planning projects where all three manufacturers are mentioned. The fact is, however, only 202 of these projects mention all three manufacturers in one specification.

417 projects are specifying a single manufacturer from this group (they may contain other manufacturers from our list of 39, but we are exploring a potential contact strategy using just these three manufacturers as our example).

Table 2 also shows us there are 778 architects who control these specifications. With some analysis, we can now see which of these architects favor one or more of these three manufacturers.

In fact, 240 architects have only one of these three manufacturers mentioned in their specification!

Armed with such information, depending which of the three manufacturers you want to pretend to be in this theoretical game, you would hatch a very different contact strategy based on your objectives as shown in Table 3.

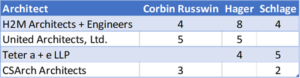

Table 3. Four random architects and the number of mentions of the door hardware manufacturers from Table 2 planning projects.

Table 3 shows us three random architects from the 778 and the number of mentions in the planning projects for these three manufacturers. If you were any of the three manufacturers, you see H2M is a highly contested battlefield. That firm favors Hager but has specified the other two. If you are any of the three, your contact strategy might be to simply “maintain” your presence with that firm. Or if you have an advantage, you might elect to navigate in a “basis of design” and surpass the leader.

On the other hand, if you are Schlage, you need to decide what to do about United Architects. You clearly don’t have a foothold in the planning projects going on in that firm. Did the firm ever spec you? Why did they stop if they did? Or, why didn’t they ever spec you if they didn’t?

The same is true of Corbin Russin toward Teter a+e and Hager for CS Arch Architects. You can clearly see that if you are going to fight for architects, mentions – not projects – is how you lay out your battleplan.

Note, too, there are many open specifications, or general outlines of what should be used in the entire dataset, where no specific manufacturer is mentioned. In some cases, the decision is left to others like contractors to determine (this is especially true in the planning stage of a project, where manufacturers have yet to be named).

Some door hardware manufacturers consider themselves “residential” or “commercial” or both; some architects have been influenced by such perceptions. This may also limit the manufacturer’s appearance in some specifications, and in a tight market, leaders encroach into the smaller manufacturer’s territory. Likewise, sometimes the smaller company will invade the larger company’s territory trying to steal share.

You can see that developing the right contact strategy to uncover opportunities in door hardware project specification really depends on WHO you are as a company and what you make (or what you want to make), as well as where you think you should be playing. It’s not just about the projects in the actual battle: it’s about the mentions.

Strategy is Everything

Developing a contact strategy for a door hardware manufacturer to approach the market depends on the company’s current position. For example, if you are one of the larger companies, your strategy may be to take share away from one of the other leaders where you now fight for share. In that case, you would fight differently than the company with the least number of project specifications in the dataset trying to gain share. In both cases, however, your competitors will be different depending on the analysis of mentions you conduct.

If a smaller company does take on a larger competitor, it would be risky. If you take on a smaller one, you may waste resources fighting for just a blip in the market share. If the currency is firms, then you must have a clear understanding of how those firms specify.

Some strategies, for example, use “loss leaders” to position themselves as leading innovators in a market, giving up profit for position.

Launching an attack on a larger competitor almost never works. Yet in all cases, creating a contact strategy is essential and a strategy must include consideration of the overall specification marketplace and other factors (i.e., maintenance of the door hardware for example, which almost is never “specified”).

For example, one facility executive noted that standardization of the spec allows their building managers to take a typical selection of repair parts with them on most maintenance calls. Perhaps finding out what the building has in it in a major renovation would work as your strategic position.

Another facility, however, cautioned by saying that standardizing is not appropriate because the purpose of the building shifts over time. Here, perhaps a tenant survey might work to your advantage, where you research what tenants want from their hardware. The facility manager noted that tenants change, requirements change, and that his job is to facilitate these changes without disrupting the purpose of the door and its hardware.

Such dilemmas seem to fall far away from the specification war. However, they become more and more important in the specification process. The key is differentiation, and it starts with mentions – or what is in the mind of the architect.

Brand Preference

Over the years, AIM has studied brand preference of architects – unaided (see our blog about this, What is a Brand?). Unaided preference means that when we do such studies, we do not provide a “list” from which the architect selects. Instead, there are blank lines and the architect fills in what comes to his or her mind when asked “the top brands I specify/recommend” for a product category. One of those categories is Door Hardware.

This research gives manufacturers a way to understand how architects perceive their products and brands, and measure continually how those brand positions change without “helping” them in their choices. It allows us a peek into the “mind” of the architect, which in turn, can help shape your strategy.

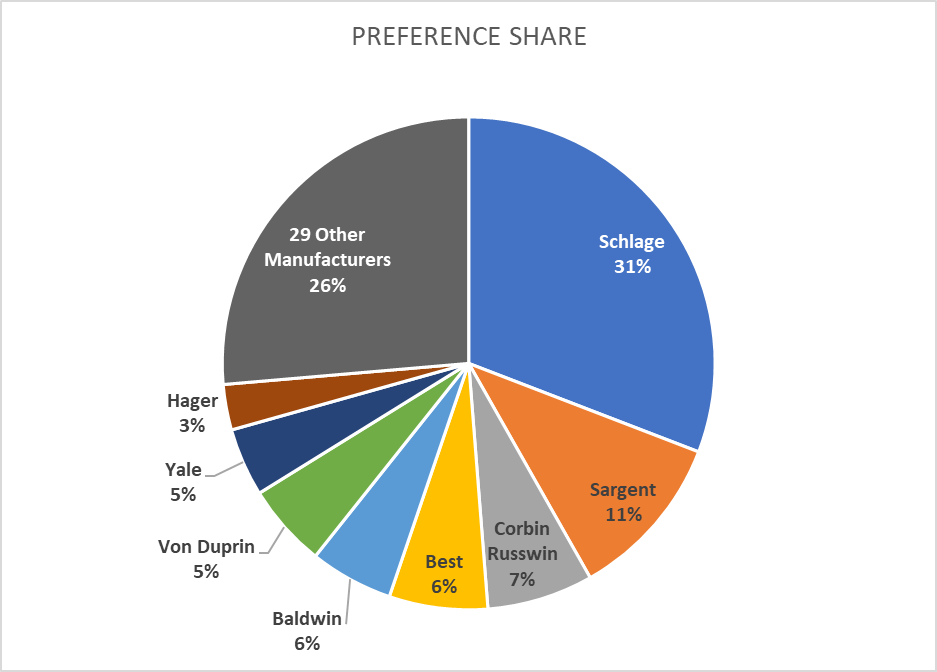

In a study of Door Hardware, eight choices appeared 74% of the time in the mind of the architect and 29 other companies account for the remaining 24%.

Chart 2. Brand preference study from AIM shows what is in the minds of architects in terms of unaided recall of door hardware brands. Architects were invited to write in their preference instead of selecting from a pre-loaded list. The result is a closer picture of what’s really in their mind.

Note that Schlage was the “brand” that came most often to the architect’s mind since the architect wrote that name into the first line of the unaided recall research. An immediate question is why does Schlage dominate in brand preference, but not in specification preference?

The answer is obvious and the nature of a brand: it can be preferred, but not selected. You might prefer to drive a Rolls Royce, but you would select something else. Brand preference gives Schlage a tremendous advantage. Hager’s advantage is in its specification strength.

Besides, Brand Preference is measuring – or trying to measure – what’s in the mind of a person. Examining the specifications as we do (and did in this case) is more of a reality check – the actual specifications of the architect.

Furthermore, consider that in some cases, “by client” was what the architect wrote down or “by planner” (in the 29 other manufacturer share of the pie) as his or her preference. In other words, no hardware brand was dominant enough to that architect, so he or she wrote down the words, “by planner.” In other categories, brands (i.e., HVAC) almost cease to exist, as the architect will write “by owner” for the preference or “by engineer.”

It is also important to know that AIM brand preference studies, which have been going on since 2008, show that while brands may come and go, solid brands stay. Sometimes (i.e., like Gruppo became Valli & Valli or Ingersoll Rand became Ives) brands morph into other brands. It’s up to the manufacturer of these brands, however, to make sure the specifying architect or interior designer understand what’s being specified. That’s the battle you fight, and one you can win with the right contact strategy.

Take Aways

We hope this exercise helps door manufacturers or any other category manufacturer to understand the power of specification analysis through mentions, not just projects. AIM is ready to help you. Please call us when you have a question. Thank you for reading our report.

_____________________________________________________

[1] Language like “Provide door hardware from one of the following national or local suppliers.” is followed by a list of 8 suppliers, with additional wording: “This list of suppliers is not exhaustive. All listed suppliers may not supply all specified products. Contact hardware manufacturers for additional authorized local or national suppliers not listed.” Imagine that type of language being used in ALL products in a specification going forward! Maybe a better question is, how long before that happens further complicating the specification process?

[2] For example, the first entry in Sweets under the category for “door hardware” talks about a company that “has been a premier manufacturer of commercial and residential plumbing products, producing a variety of durable, reliable and beautifully designed products for everything from private homes to five-star hotels.” If you Google “door hardware manufacturers” you get a list as one of the results here that is closer to what we find in our database of about 49 companies.